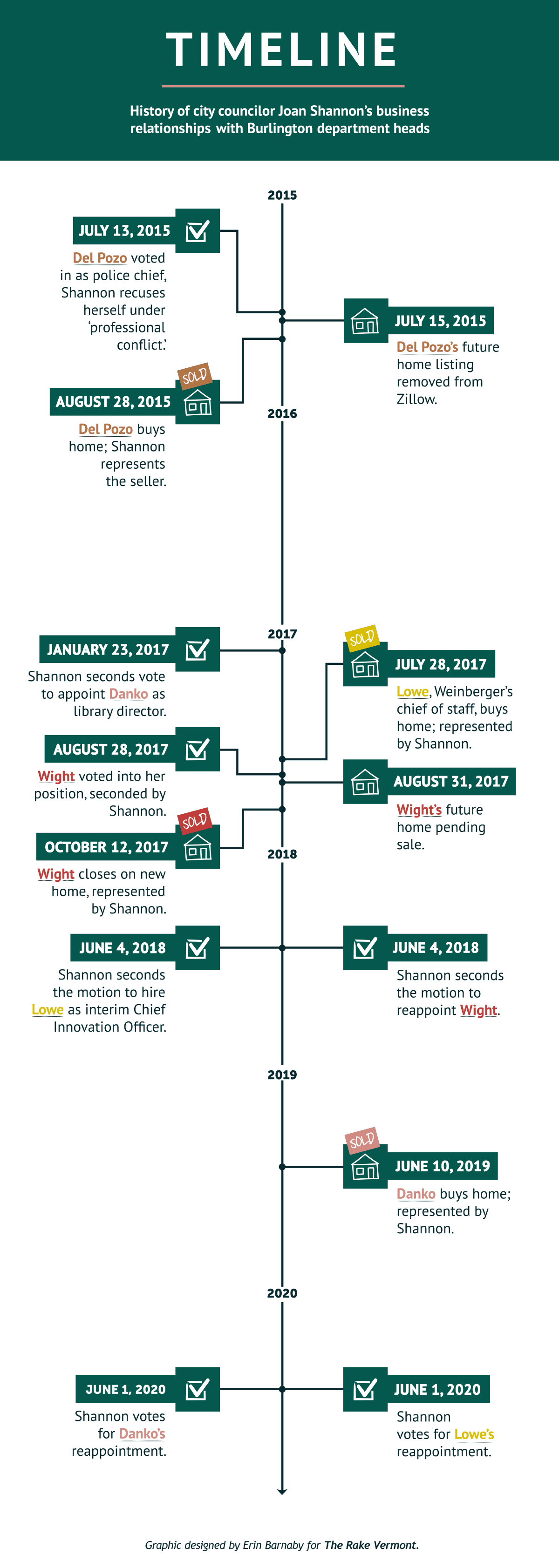

In 2015, Burlington City Councilor Joan Shannon recused herself from voting on the appointment of former police chief Brandon del Pozo, citing a professional conflict of interest. In her role as a realtor, she was representing the seller of a home del Pozo was about to buy. Yet, a recent investigation by The Rake Vermont reveals that Councilor Shannon, in what appears to be a conflict of interest, used her position to sell homes to three other city department heads from 2015 to 2019, subsequently voting for their appointment or reappointment after she collected her commission.

The City of Burlington’s charter says that “No City officer shall participate in any fashion or cast a vote on any matter in which either a direct or indirect conflict of interest is present.” As stated by the Vermont League of Cities and Towns, “in general terms, a conflict of interest is an incompatibility between the private and public interests of a public official.” Would these sales fall under either of those definitions of a conflict of interest?

According to Zillow.com and Redfin.com and cross-referenced with the city’s property database, Shannon assisted Fletcher Free Library Director Mary Danko in buying a home in 2019. Shannon voted to reappoint Danko less than one year after the purchase. Shannon also helped Burlington’s former Chief Innovation Officer, Brian Lowe, buy a home in 2017. Less than a year later she seconded the motion to vote him in as interim Chief Innovation Officer.

Shannon was also the realtor for the current director of Burlington’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Waterfront, Cindi Wight. In August of 2017, Shannon seconded the motion to appoint Wight to her position three days after closing on Wight’s new home. Shannon went on to work closely with Wight and Danko, first as a member of and since 2020 as the chair of the Park, Arts, and Culture Committee. In fact, they all met for an official city meeting of the Parks, Arts, and Culture Committee only six days after Wight closed on her house and Shannon had likely received her commission from Wight.

We asked Directors Wight and Danko if they would comment on this potential conflict of interest, and we were told by the Mayor’s office that “because the inquiry is in regards to a personal matter and not city business or work” they would not be accepting an interview. However, the city of Burlington did not deny that these business relationships existed.

City Council President Max Tracy, who knew about the del Pozo and Lowe home sales but not Wight or Danko’s, disagrees with the Mayor’s assessment that this is not a city issue. “I see the real estate transactions as being directly related to the council vote. I don’t know that those folks would have relocated if they weren’t confirmed [by the council].” Wight came from Rutland, and Danko came from Sunapee, New Hampshire. While Shannon responded to our initial email asking for an interview, she did not respond to any of our questions or follow up emails, so we cannot share her perspective here.

Shannon has been very public about her professional conflict of interest with del Pozo, recognizing the conflict and removing herself from voting to hire him in 2015. In 2019 she was not present for the reappointment vote of all department heads, including del Pozo’s contested reappointment, and there is no record of why she left council chambers and did not return until after the vote. When Shannon represented the home seller, as she did with del Pozo’s 2015 purchase, she separated politics from business.

Real estate transactions, which often require realtors, lawyers, and banking professionals, are highly technical, requiring specialized licenses and training, and can often come across as being nontransparent to those outside the industry. For example, technically a home buyer’s realtor does not get paid a commission by the buyer themselves. In most real estate transactions, the property seller pays the commission (either a flat fee or anywhere from 2-5% of the total sale price) of both realtors. This payment comes from the seller, out of the purchasing price of the home and the thousands of dollars in closing costs and taxes that the buyer pays. Part of what a client pays for is a realtor’s expertise and customer service skills.

Shannon has been conspicuously silent on her professional relationship with the three other department heads. It is not clear why other city councilors did not know about these other sales, nor why this potential appearance of a conflict of interest was not brought to the public. While Shannon may not have technically been paid her commission directly from three city directors, she directly benefited financially from those sales.

Buying or selling a home is often one of the largest financial commitments that someone will make in their lifetime, and realtors often build close relationships with their clients. Martha Nowlan, a self-described anti-capitalist Vermont realtor since 2017 who believes housing should be guaranteed for everyone, recognizes the importance of those close relationships. She sees how close relationships can develop between realtor and client and the potential pitfalls of mixing business with the personal.

“Buying a house is a huge decision and it’s really personal,” Nowlan says. “Anyone who tries to make it seem like it’s just a financial decision, it’s obviously not. It’s way more than that…It’s going to impact where you spend most of your time. It’s definitely important to have a trusting relationship.” Shannon’s strong relationship-building with clients shines through on her numerous five-star Zillow reviews.

One of the most common ways for realtors to gain new clients is through referrals. A former client or friend learns that one of their friends is looking to buy a home and suggests their realtor. Nowlan told The Rake Vermont that she finds that this strategy “leads to more trust and more lasting relationships.” She adds that for anyone in real estate or sales, “the best thing you can do is have clients who come back to you for the next time and who refer people to you.”

Because the Mayor’s office did not allow us to speak to the two remaining department heads, we do not know how Shannon was hired by three different department heads. According to the Vermont Secretary of State’s office, there are over 1,300 individual realtors licensed in the state of Vermont. Over 500 of those realtors are based in Chittenden County, and over 100 are in Burlington. It’s possible that if it were not for Shannon’s position as a city councilor, interviewing and hiring city directors, she would not have been able to connect professionally with these three department heads.

Referrals are important in the real estate industry not just for finding new clients, but also for realtors to work collaboratively with their peers. In Nowlan’s case, her parents asked her to help them buy a home, but Nowlan did not want to mix family and business, so she referred her parents to another realtor. This is a common practice within the industry when a realtor does not feel comfortable—for personal or ethical reasons—working with a specific client. This arrangement benefits all realtors, as common practice holds that the one who refers clients often receives 20-25% of the final commission without having to do the real estate work. In Nowlan’s case, she chose to have her portion of the fee be refunded to her parents.

While Nowlan doesn’t believe that Shannon’s actions were illegal or unethical within the many different statewide and federal real estate regulatory bodies or within the ethical guidelines of local or national real estate organizations, one has to wonder why Shannon did not refer these three department heads to one of her hundreds of colleagues when such a relationship would create at a minimum the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Adam Roof, chair of the Burlington Democrats and former Shannon campaign manager, did not respond to our request for comment, nor did he respond to questions surrounding the two home sales that Tracy was unaware of for several years. When Roof was hired by the city in 2019 to lead BTV Ignite, a quasi-city department, there were questions around his own conflict of interest. Roof said at the time in Seven Days that “it’s not a goal to eliminate conflicts; the goal is to declare them.”

Ted Brady, Executive Director of the Vermont League of Town and Cities, told The Rake Vermont: “If a citizen is unhappy with a municipal body’s conflict of interest policy or a particular conflict of interest decision, there are several remedies. Most notably, using the power of elections. But also by attending public meetings to share their concerns, utilizing the court system, and I also believe the state ethics office takes complaints on all government officials—including municipal officials.”

Up until 2018, Vermont had little oversight over elected officials. The Vermont Constitution included a Council of Censors, an oversight panel that had very limited authority; its main tool of oversight was writing advisory opinions. They met sporadically from 1785 to 1869, when the Republican-controlled State House disbanded the Council of Censors during the state Constitutional Convention of 1870. In 2017, in response to a Center for Public Integrity report which gave Vermont a D-minus rating regarding the state’s oversight to deter state corruption, Governor Phil Scott created the State Ethics Commission. Yet this new commission only had the authority to make referrals and track complaints, leading the Coalition for Integrity to call it a “toothless ethics agency [that] serves no purpose.”

Given the options laid out by Brady, it seems very unlikely that any Burlington official will ever be investigated or censured for apparent conflict of interests. Shannon is popular in her district, regularly receiving 60% of the vote when running opposed, making that an uphill battle for any electoral opponent. Citizens using the court system would also face challenges, especially for those who do not have access to legal or financial support, as court filings alone range from $90-$300. Relying on the council to censor one of its own members would also be a tall hurdle, as it has not occurred in recent memory, if ever.

When asked, Council President Tracy said that the council has no clear path for investigating potential conflicts of interest like this. “There’s no policy, there’s no procedure laid out for when things like this come up,” Tracy said.

In a council meeting on August 26, 2019, Shannon, as chair of the charter committee, presented a resolution to modify the city’s conflict of interest policy. In that meeting Shannon said, “We thought it was important to have some flexibility because there are cases where you can disclose pretty directly what your conflict is and there are other situations where you cannot.” Councilor Jack Hanson acknowledged the change was watered down, as the resolution did not discuss what would happen if a conflict of interest was never addressed in an adequate amount of time. The resolution, while encouraging a councilor to provide more details about a conflict of interest, imposed no penalties and kept the policy as one of self-reporting on the part of councilors. The vote passed unanimously.

Emily is a writer and organizer on the editorial collective of The Rake Vermont.