With the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing set for February, Vermont is well represented by multiple athletes, most of who are skiers or snowboarders. Whether the athletes grew up here, presently reside or train here, or are current or former attendees of local colleges or universities, the state punches far above its weight in Olympic contenders. In winter Olympic history, there have been over 200 athletes and over 30 medalists with some Vermont connection.

Reaching this level comes at a high cost, both for the athletes and the state as a whole. Expensive private elite training academies may block poorer residents from competing at the highest levels, and increased conglomeration of ski areas by large corporations has priced out many Vermont residents, preventing a majority from even enjoying snowsports recreationally.

If you were to sample the Vermont contingent of Olympians, you’d find some common trends. Most attended costly schools that specialize in snowsport training, starting as a pre-teen or early teen. Many grew up in affluent, high-income towns, or are part of families that own second homes near ski areas — helpful, considering Olympians are not well compensated and experience financial struggle. Many gained access to elite training, leading to college athletic scholarships, and after graduation, entry into selective work-live training programs, or were recruited into the National Guard for the purpose of preparing themselves for the Olympics and world championship events. There are even multi-generation winter Olympians, some of whom own a ski hill (though, in fairness, Cochran’s is one of the only truly affordable places left to learn to ski in the entire state).

Now, that doesn’t mean these Olympians are undeserving. Qualifying for an Olympics, particularly as a United States skier or snowboarder is extremely difficult. You must be among the best in the country to do this and it takes years of training and competing for a limited number of spots. This isn’t a team full of Prince Hubertus of Hohenlohe-Langenburgs. But, it’s not exactly inclusive, is it? Only those who get access to academies and training are usually able to press forward toward Olympic glory. And, the industry catering to elites makes it harder for a majority of the state to even have the chance to enjoy a day at the slopes.

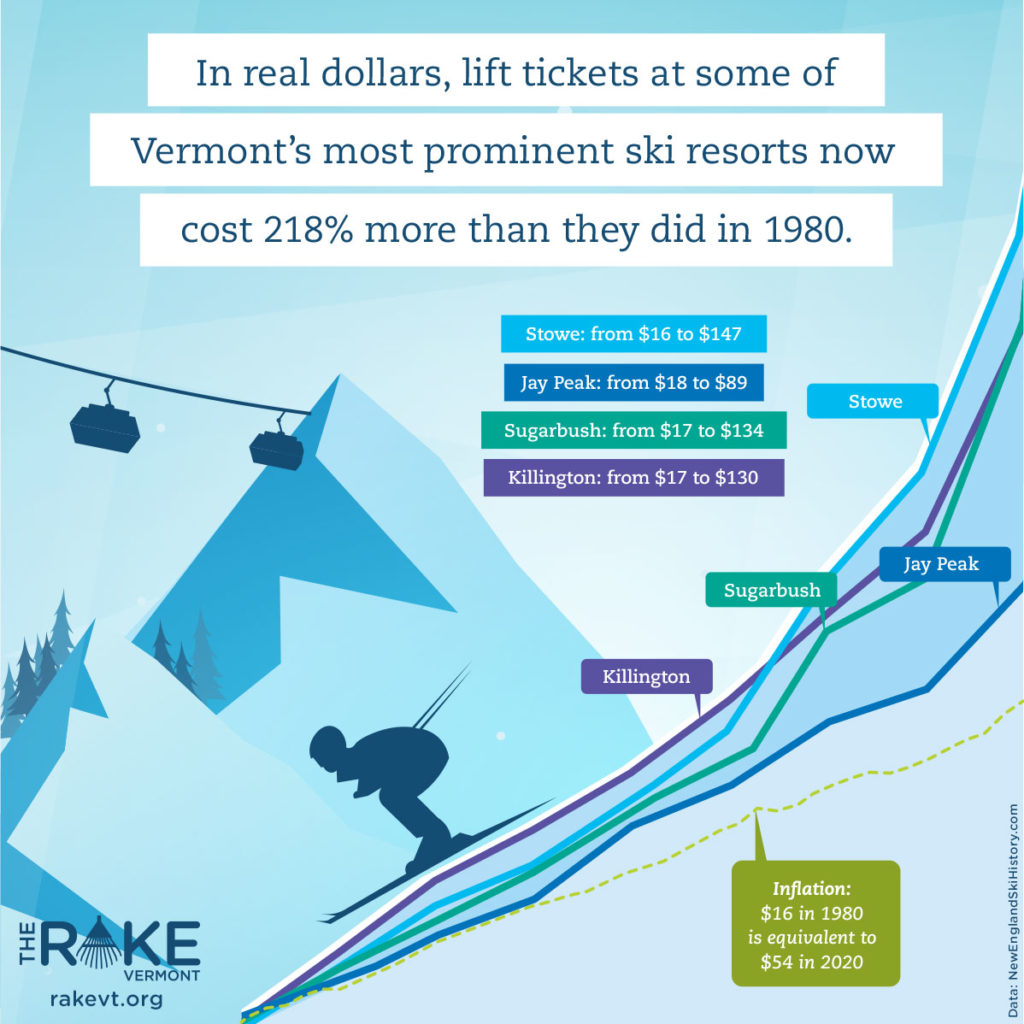

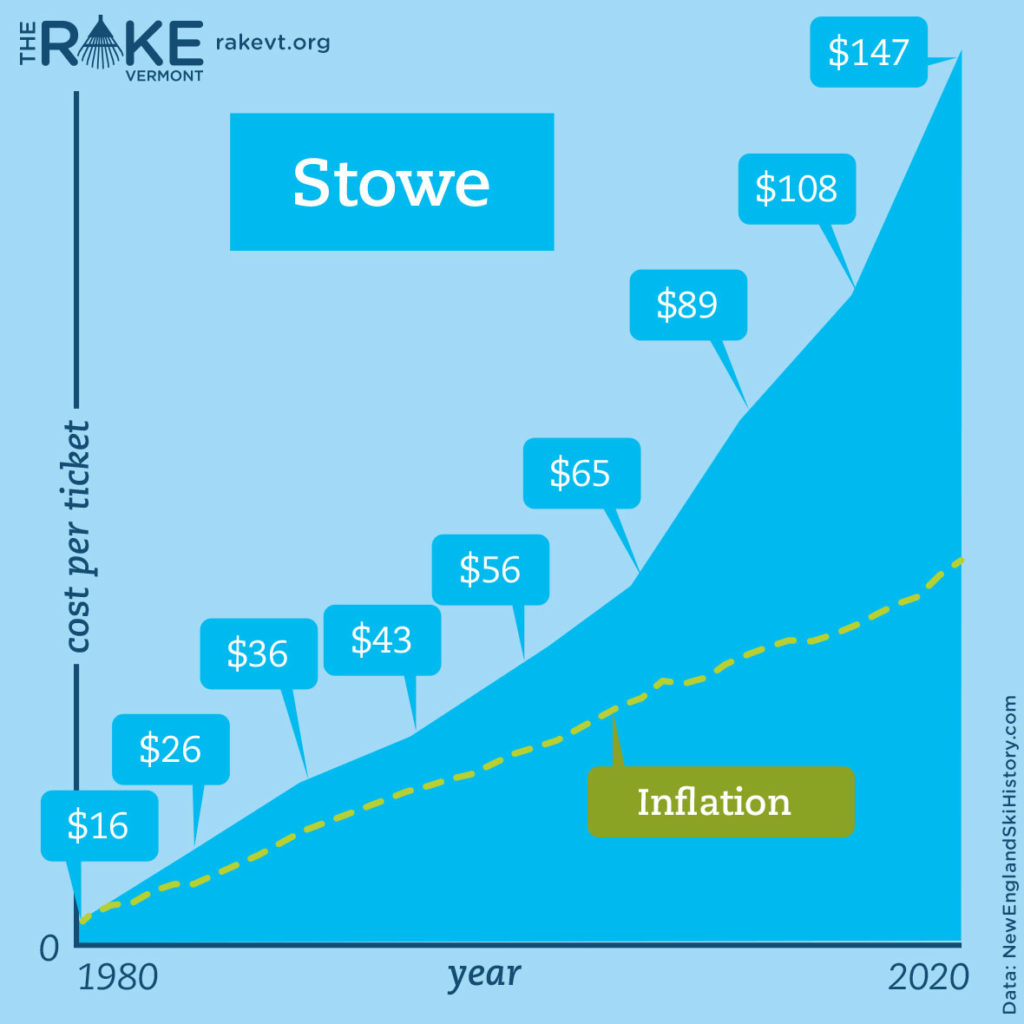

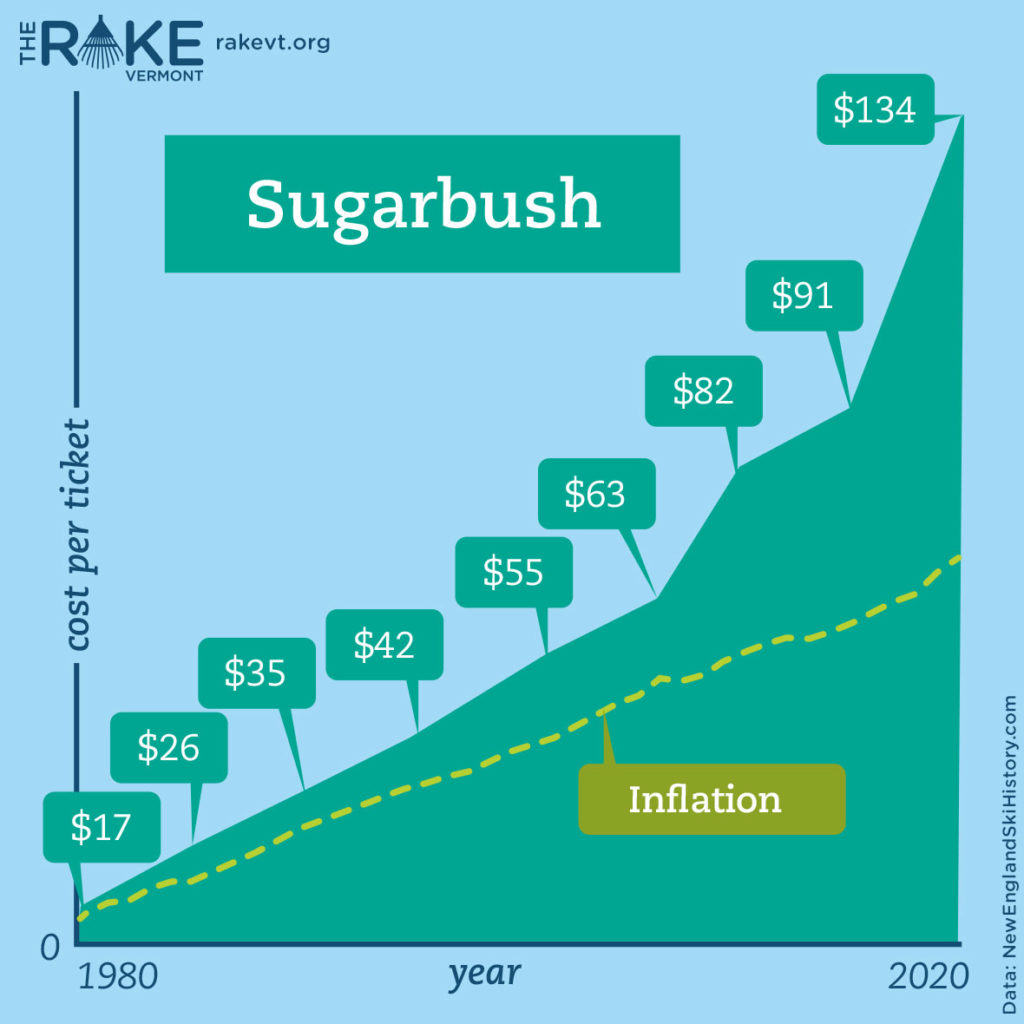

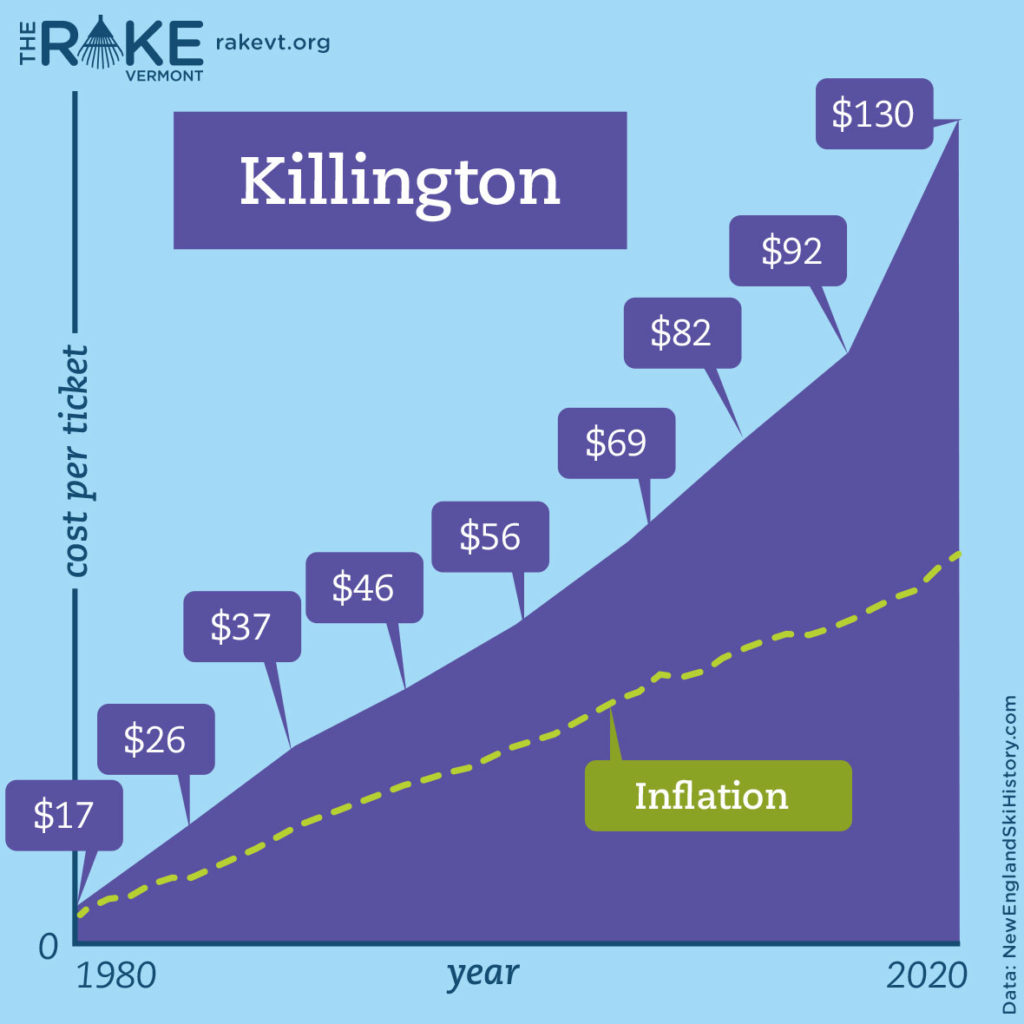

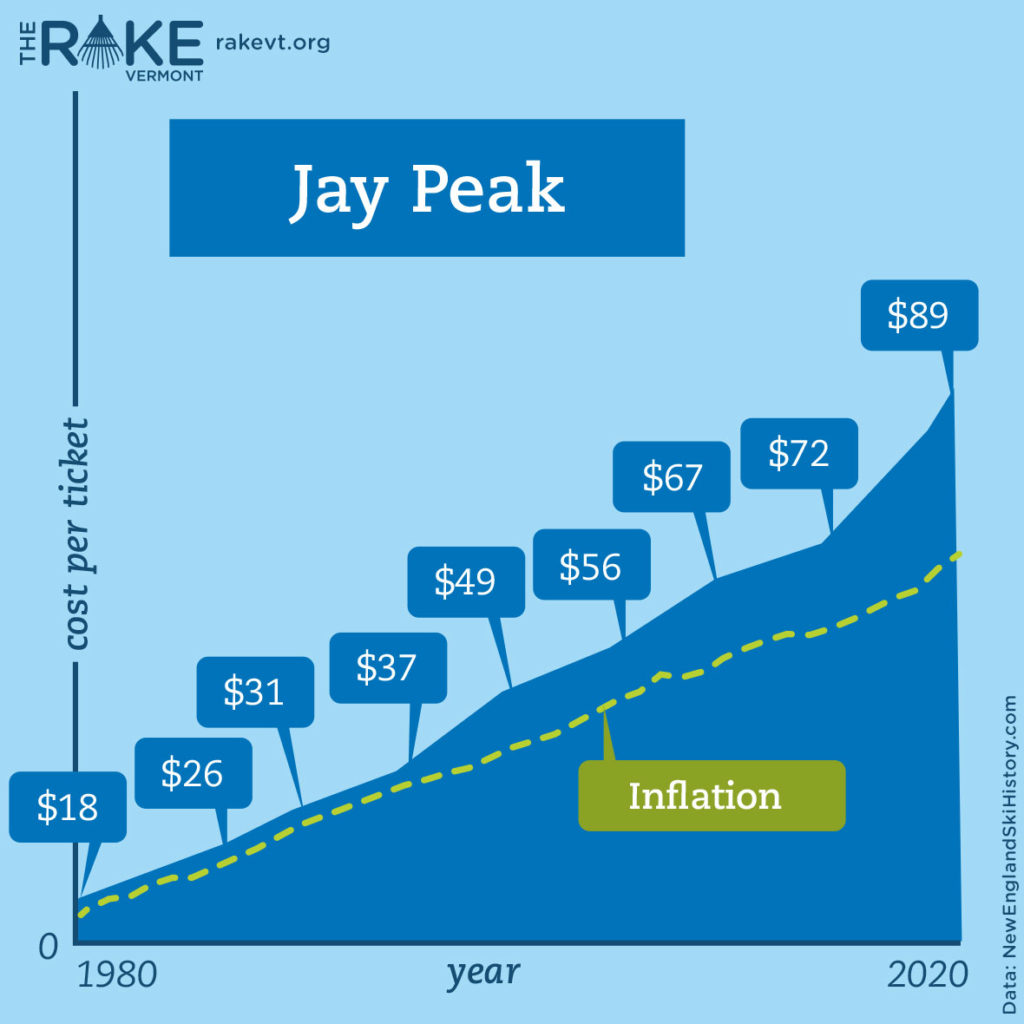

Downhill skiing has long been associated as a sport for the upper classes. That wasn’t always the case. Vermonters could ski at resorts like Stowe for $7 a day in the late 1960s, and lift tickets averaged about $20 in the 1980s. A whole vacation might run you around $275. There used to be many more modest ski areas in the state. Compared to the current 19 consolidated and financialized resorts and ski areas in operation today, nearly seven times as many ski areas, ranging from rope tow hills with one or two trails to resorts of varying sizes, have closed throughout the state. Many Vermonters over age 60 learned to ski on hills like those, before graduating to more challenging terrain. Even factoring in inflation, and the innovation of high-speed lifts and snowmaking capabilities, you’re still paying a lot more than you should.

A season’s pass can alleviate some costs, but it requires a big commitment. To find a day rate, you have to find deals online directly from the resort or try third-party sites as if you’re searching for airline flights. The average cost of a single-day lift ticket purchased directly online in the month of January at Jay Peak is $87. $89 at Bromley. $121 at Stowe. $127 at Sugarbush. $132 at Killington. Others like Mount Snow, Okemo, and Stratton also see average daily prices online hover in the $100 range. Some affordable options for under $70? Smuggler’s Notch ($56), Bolton Valley ($60), and Magic Mountain ($64). Cross country skiing facilities on the other hand, without the need for chairlifts, provide many options for adults at around $25 or less.

Just as we’re funneling our Olympic hopefuls into elite training reserved for a few, the skiing and riding industry continues to consolidate ownership into the power of a few. It’s not new. First, it was the American Skiing Company (Killington, Mount Snow, Haystack, and Sugarbush) in the 1990s. Then the Powdr Corporation (Killington, Pico). Now, Vail Resorts owns Stowe, Mount Snow, and Okemo, and 37 others across the country. Alterra Mountain Company owns Stratton and Sugarbush, two of 15 in its portfolio. Jay Peak, thanks to the EB-5 scandal, is for sale, with several buyers interested, including Alterra. If you’re seeing a pattern between conglomerate-owned resorts and high lift ticket prices, you might just have identified the problem.

So, just go to one of those other, cheaper resorts, right? Sure, if you live within a reasonable distance of them. While some of the independent resorts are banding together as a cooperative, that doesn’t solve the fact that the state’s residents have to sit by and watch as capitalist interests pull more and more people out of activities that all, including Vermonters with disabilities, should be able to enjoy.

It’s important to remember, many of these resorts are on land leases with the state, as they are often situated in state parks. There could be a greater demand to control ticket prices and access for residents on a governmental level, though organizing around would be a difficult and niche challenge. Non-profit co-ops could be a path forward, and Mad River Glen chugs along, but as the City Market of ski resorts, they still don’t allow snowboarding.

At multi-million dollar price tags, Burke Mountain (another EB-5 victim), and a failed country club-style resort, Plymouth Notch, are available for sale. Mount Ascutney is sitting around in need of a revival. Why should these go into the hands of private ownership?

The question we should be asking ourselves in the face of inequality in the ski industry is – what does combating inequality look like? Some ideas include: Public ownership of resorts, more free, public recreation areas with ski hills and Nordic trails in towns across the state, and the expansion of free equipment and use for communities, especially BIPOC participation, by eliminating cost and racial barriers to the sport. Resources and environmental impact permitting, more night skiing would be beneficial to a lot of service workers. As for those elite training schools, how about taking a Cuba-style approach to sports and training, making it available to everyone, and allowing those with standout ability to flourish and continue towards Olympic greatness without ever being priced out?

Seeing Vermonters continue to perform well in the Winter Olympics is a point of pride. It’s nice to see people with some connection to the state succeed at the highest levels of sport. But, if we’re not even trying to preserve a future where everyone has the opportunity to ski or ride, where communities have control of our slopes, our Olympic pride is shallow and short-sighted.

[Ed. note: On February 1, 2022, the New York Times published an article on Mount Ascutney in which it details the town buying the mountain and turning it into a community-run ski area.]

Data visualization by Erin Barnaby. Photo in top illustration by Joe Shlabotnik, BY-NC-SA.

Matt Moore is a writer from Vermont. He is on the editorial collective of The Rake Vermont.