In Part 2 of this series, we look at how Vermont’s incarcerated workers are exploited by the State, the Vermont Department of Corrections, and the many nonprofits and municipalities that employ them. Read the other parts of this investigative series here.

As discussed briefly in part 1, there are many employment options for Vermont’s thousand-plus incarcerated workers. These options include internal prison work, which keeps the prison functioning day to day, being leased out to local municipalities and nonprofits for as low as 25 cents an hour, or being part of a work-release program with the opportunity to earn prevailing wages.

With the exception of the work-release program, these employment options pay on average under one dollar an hour, or less than one-twelfth of the state minimum wage. The best-paid internal incarcerated workers serve as under-trained social workers to their peers through a pilot program called Open Ears, which started in 2019 and pays workers $7 for one day of work.

Internal Prison Work Saves Vermont Millions of Dollars

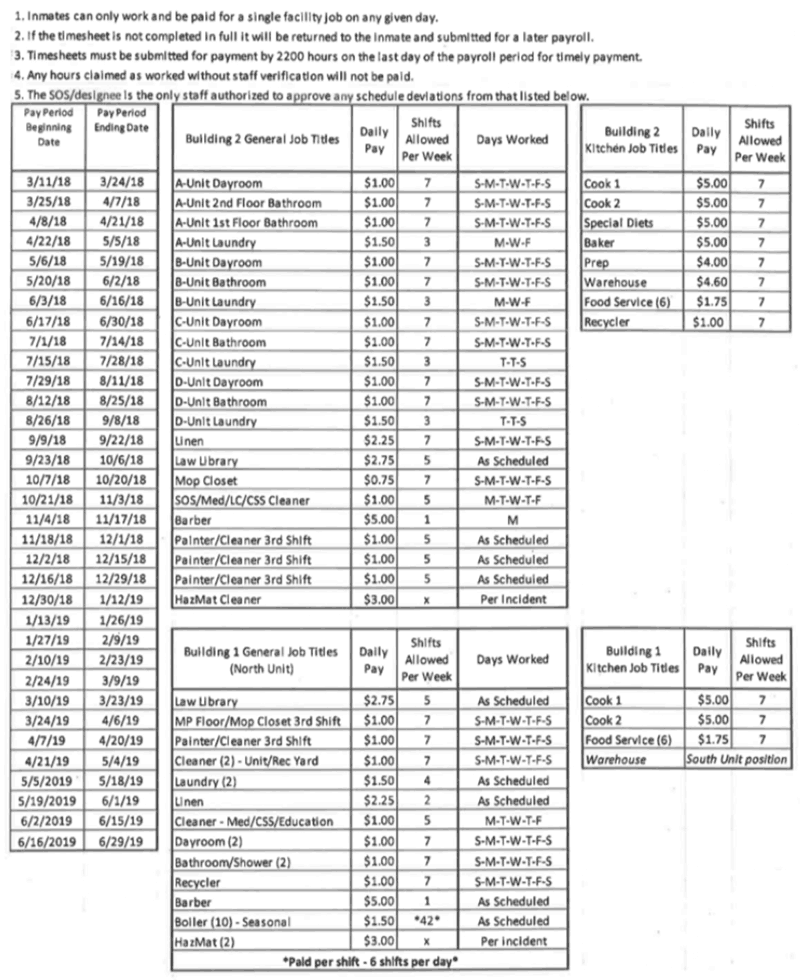

Incarcerated people in Vermont are often used to shore up labor shortages within the DOC. They are put to work washing laundry, cleaning floors, cooking and serving meals, organizing prison libraries, or making basic facility repairs. These positions, vital to the operation of the facilities, pay far less than what rookie DOC Corrections 1 Officers make, which starts at over $19 an hour. As seen in the image below from 2018 to 2019, prisoners were paid a maximum daily rate of $5 a day for internal prison positions. It is not clear how many hours constitute a shift.

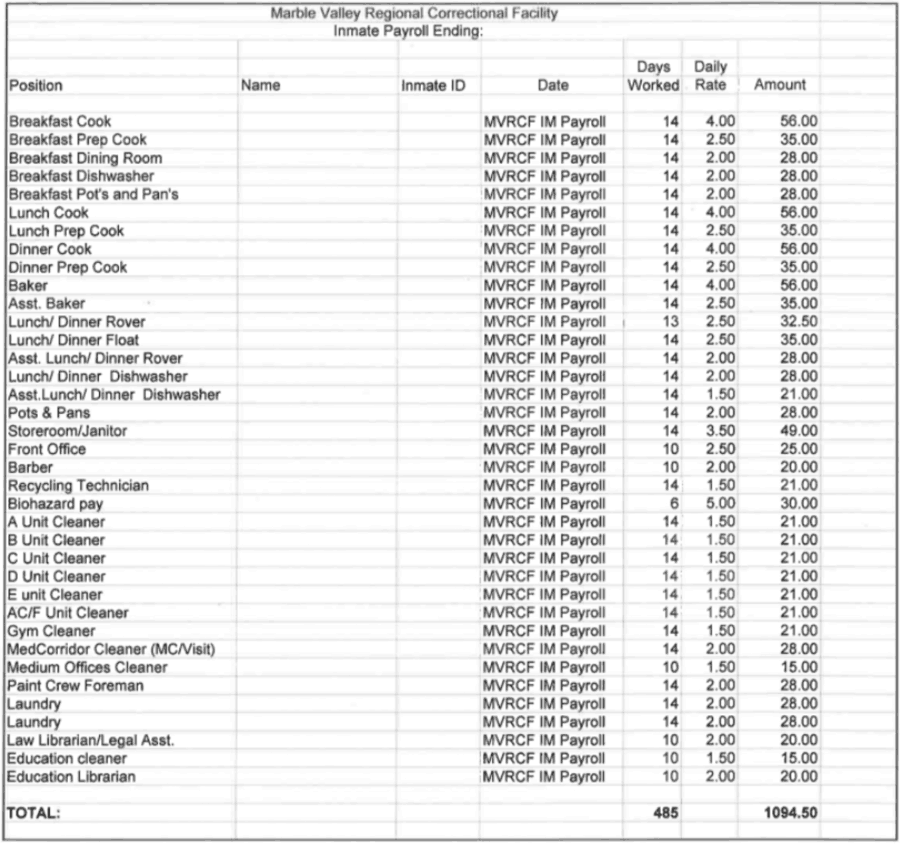

While Vermont DOC refused to give us payroll information for incarcerated workers throughout the state, we were able to find a single month of payroll for Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility.

Data shows that for a single month, Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility paid incarcerated workers a total of less than $1,100 for 485 work days, an average of $2.25 per work day. If this work had been performed by workers at Vermont’s minimum wage, it would have cost the DOC over $70,000.

By using prison labor, it appears that the DOC would save something like $860,000 a year in a single facility. Even with conservative estimates, it would appear that the DOC saves millions of dollars every year across their seven correctional facilities on payroll and benefits by utilizing prison labor.

The potential cost of paying incarcerated workers for their labor at market value is what derailed an attempt by California legislators to pay incarcerated workers a commensurate wage. Falko Schilling, the advocacy director at ACLU Vermont, takes issue with fiscal arguments against paying incarcerated workers. “If we can’t adequately compensate people who are incarcerated for their labor, we need to rethink what that system looks like to ensure that we can,” he said. “We should not be building systems based off of labor which is not adequately compensated.”

The Vermont Offender Work Programs Exists to Lower Government Costs

Vermont Offender Work Programs (VOWP) is made up of three smaller programs that hire incarcerated workers both inside and outside prisons: Vermont Correctional Industries (VCI), Community Restitution Service Units (CRSUs), and Correctional Facility Work Camps. VOWP provides labor far below market costs to Vermont municipalities, regional utility companies, other public entities, and local nonprofits.

VCI has established different kinds of labor to be performed by incarcerated workers. They can make license plates, metal signs, work in the print shop making items like business cards and brochures, or produce furniture in the wood shop for governmental organizations and nonprofits.

Job Titles and Hourly Wages

(Hover over the chart for more details. The current minimum wage in Vermont is $12.55)

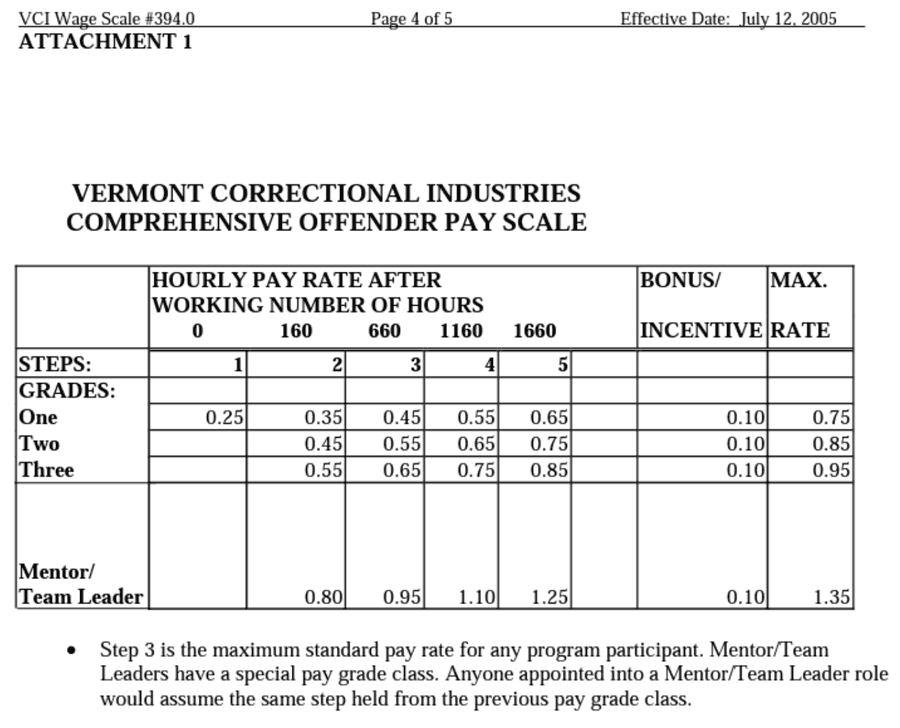

According to a pay scale that has not been updated in nearly two decades, Vermont’s incarcerated VCI workers, if in a leadership position, can make up to $1.35 an hour. A typical worker makes only $0.60 per hour.

To put this another way, an incarcerated worker who works 40 hours per week for 52 weeks a year will make as little as $1,000 per year and a maximum of $2,000 per year. Even if they become a mentor, an incarcerated worker’s pay will never reach even $3,000 per year. The DOC can also withhold up to 70% of this income for numerous reasons mentioned below. The federal poverty line for an individual is $13,590.

Another division of VOWP is the Community Restitution Program, also known as the Community Service Work programs. In this program, an imprisoned person works for no pay to “to successfully make amends to the community through structured work contracted with municipalities, state agencies, and local non-profit organizations.” A former directive describing fees for Community Service Work stated that this work “must be delivered at less than market cost in order for [it] to be valued by the community.”

Some incarcerated workers aren’t paid in currency at all for their work. Instead, people imprisoned at work camps can be paid with “good time,” which is the possibility of a shorter minimum and maximum sentence. People in prison who have not been convicted of a “serious” crime can receive a maximum sentence reduction of seven days each month. If a prisoner is working toward a shorter sentence, this suggests the sentence itself is not one based on a court’s determination of justice but is rather a negotiable transaction. Notably, incarcerated workers cannot earn good time solely for good behavior – part of the requirement is that they work for no wages.

Rehabilitation or Cheap Labor?

The DOC states that these programs prepare people incarcerated in Vermont to “be contributing members to our communities and economy” once they are released from prison. Schilling disagrees.

“When we look at the challenges that folks face when they are trying to re-enter their communities, financial burdens and barriers are a major concern,” Schilling said. To support formerly incarcerated people, “increased compensation is something that needs to be addressed so that folks have those resources to most successfully enter their community and also support themselves and loved ones while they’re incarcerated.”

While couched in the language of rehabilitation by its proponents, the only activity measurably performed by these programs is the provision of extremely cheap, pliable, coerced, and non-union labor. Given the economic imperative for owners to compensate their laborers as little as they can manage to, taking advantage of incarcerated workers would be a significant advantage against one’s competitors in the market. This is why state law restricts the use of incarcerated labor to the public and nonprofit sectors. As VCI puts it, that restriction advances the goal “of protecting private companies from unfair competition.” The only potential unfairness recognized by the state is that which would be suffered by business owners without access to cheap or free labor, and not those performing the labor itself.There is only one way for Vermont’s incarcerated workers to make prevailing wages, and that is the Work Release Program. There are several strings attached, including that only the commissioner or supervising officer can grant permission for workers to participate in the program and that their employment cannot cause the “displacement of employed workers.”

In this program the State of Vermont acts as a temporary hiring agency and charges a monthly supervision fee paid by the incarcerated person for this privilege. According to a record request from June 2021, supervision fees for the 2020-2021 fiscal year totaled over $600,000, of which $310,000 was collected.

It is explicitly written in the Vermont statute that the prison commissioner controls the workers’ paychecks, and according to a separate directive, they have the authority to deduct or garnish them up to 70 to 80%. These deductions pay for federal, state, and local income tax, family support for dependents, a victim’s compensation fund, fines imposed by the court, any loans received from the DOC, any damage to state-owned property, and for room and board.

While the Vermont Department of Corrections terms this “a fair and motivational compensation system,” Vermont ACLU’s Schilling sees the scheme as a cause for concern.

“When we look at the labor within the Corrections Department here in Vermont, I think that one of the biggest concerns is that folks are just being inadequately compensated for the labor,” Schilling said. There are significant “financial burdens that are put on people while they’re incarcerated, both to pay for fees, to pay for things like the ability to contact and stay in contact with loved ones, … supporting others on the outside and then also rebuild their lives when they reenter the community.” Too often, instead of rebuilding, people in prison are at risk of being unable to meet their basic needs.

In parts 3 and 4 we will look at the private corporations that make significant profit off of workers’ basic needs.

Writer’s Note: Our investigation met considerable resistance from the Vermont Department of Corrections. We made several record requests, including to inspect state contracts and prisoner payroll, and each time we were told that this would cost thousands of dollars, as all documents are either in paper and/or scattered throughout the state.

This is a common tactic that successfully prevent outside oversight of the DOC. By not digitizing data or even using basic software to keep track of data, they are able to circumvent record requests like ours. Additionally, what little information is released, like the yearly DOC budget, does not list line items that correspond to pay to incarcerated workers.

The data in this article has been peeled from other record requests and documents found scattered on the internet. Sources will be linked or displayed as necessary.

*This series will follow the Marshall Project’s editorial guide for words we use when covering people and incarceration, such as “incarcerated people,” “imprisoned people,” and “people in prison.”

Emily is a writer and organizer on the editorial collective of The Rake Vermont.