In the fifth and final part of this series, we examine how local Vermont municipalities, utilities, non-profits, and even school districts use prison labor to shore up their own labor and budget constraints. Read the other parts of this investigative series here.

Vermont towns and nonprofits benefit from the Vermont Department of Corrections by using their groundskeeping work crews, a worker-lease program through the Vermont Offender Work Programs (VOWP). While COVID-19 has put a years-long hold on incarcerated Vermonters performing physically grueling and sometimes dangerous labor for little or no money, dozens if not hundreds of Vermont organizations have used this labor as a way to save money, creating an incentive for municipalities to over-police in exchange for cheap labor.

The Vermont Department of Corrections does not shy away from touting the use of these work crews, which reach “nearly every town in Vermont, and many of the nonprofit agencies, ranging from food shelves to public libraries,” according to their 2019 budget presentation.

While most of this work involved grounds work such as mowing, lawn maintenance, and snow removal, some contracts include other maintenance work that is historically performed by fully paid laborers, like roof repair, repainting buildings, or in one instance, packaging potatoes for a Vermont food bank. Some incarcerated workers were transfer-station attendants for the town of Wolcott, and others were assigned to “assisted operations” at Lamoille Regional Solid Waste Management District facilities. In another instance, the Green Mountain Cemetery in Montpelier used incarcerated workers to dig foundations and pour cement.

Multiple record requests reveal that Vermont towns, nonprofits, local utilities, and religious institutions have used work crews to lower their own labor costs. This includes Meals on Wheels of Lamoille County, Vermont State Housing Authority, Chittenden County Transportation Authority, Salvation Army, and the United Church of Irasburg, to name a few.

These work crews can consist of one of three types of workers: incarcerated workers paid less than a dollar an hour, incarcerated workers who, similar to indentured servants, are paid with a shorter sentence, or people engaging in unpaid community service in lieu of incarceration. They are overseen by the Court and Reparative Services Unit (CRSU) and the Vermont Department of Corrections often charges a fee to organizations utilizing this free labor. While those engaging in community service are not currently incarcerated, local Community Justice Centers, which are funded by State’s Attorney offices, will use the threat of prosecution and jail time as a means of compliance.

Susan Alexander, a manager at Lamoille Regional Solid Waste Management District, is a big proponent of the program and was disappointed when the program was curtailed. In an email, Alexander wrote, “Unfortunately due to CV-19 we have not been able to utilize this program as much as we would like!”

These labor programs are funded under Progressive, Republican, and Democratic administrations and voted for by the three parties’ politicians. Our investigation found that the fees for these services vary wildly from one municipality or nonprofit to the next and can, at the discretion of a Corrections Financial Manager, even be “zero-dollar contracts.”

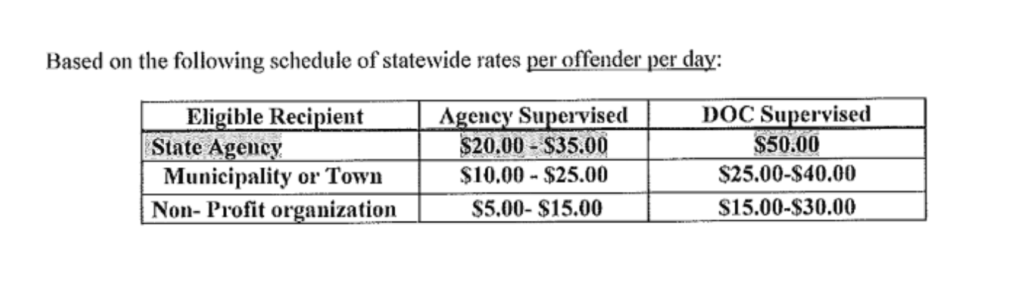

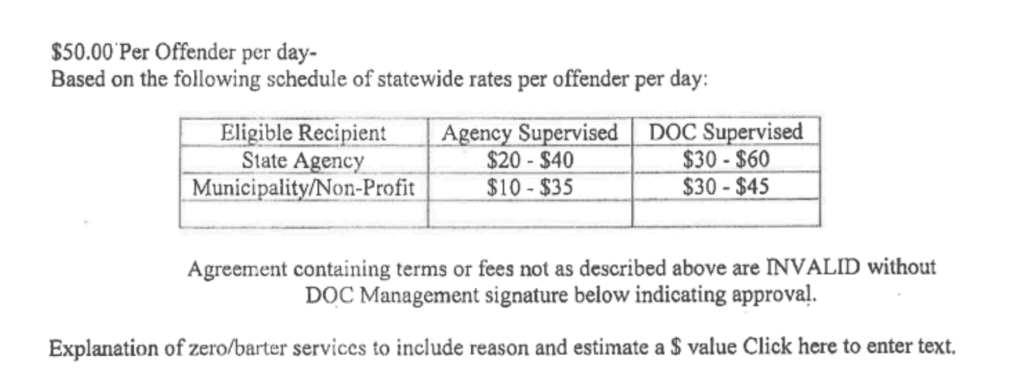

Fees from two different contracts.

The Rake compiled over two dozen work crew contracts throughout the state of Vermont from 2014-2021 and found many disparities. Contracts stipulated that the Vermont DOC be paid anywhere from $5-$100 a day per worker and sometimes just a flat fee. These contracts did not always follow the above rates, and it is not clear how rates are determined, as some municipalities were under-charged with nonprofit rates, while some organizations were charged double or triple written rates.

Other contracts, such as the 2017-2018 contract with Windham Solid Waste District, don’t involve any amount of money. The waste district instead bartered for incarcerated Vermonters’ labor in exchange for free trash and recycling removal.

Burlington’s Use of Incarcerated Labor

The city of Burlington used the VOWP extensively from 2011 until 2020 under the administrations of Mayors Kiss and Weinberger. A contract signed in 2017 by former Burlington Parks, Recreation & Waterfront Director, Jesse Bridges, shows the work expected and payment per worker.

From 2018-2020, Burlington paid over $70,000 for incarcerated labor, saving the city hundreds of thousands of dollars in labor costs, as these workers did not receive benefits nor were they paid Vermont’s minimum wage. Current parks department Director Cindi Wight, in a June 2020 email to the DOC Director Jim Baker, acknowledged that the only reason Burlington ended the program was due to COVID-19 budget cuts and not for any moral or ethical reasons.

One former Burlington parks department employee, a recent, pre-COVID seasonal worker, said he had firsthand experience of these work crews. Through messages with The Rake, he noted the differences in treatment and conditions for incarcerated workers.

“While the seasonal and full-time city employees would use walk-behind Bobcat mowers and weed whackers, work crews would use push mowers. My boss would often assign them to hazardous or undesirable sections, such as Lakeview Cemetery’s steep hills or its hedges with poison ivy growing underfoot,” he said.

This former parks department employee said that work crews would either show up with their own transportation or be dropped off by a corrections officer. He also recounted that in a rare instance, one of the workers on the work crew would work for free until noon and then, as a seasonal employee of the parks department, would be paid for doing the same kind of tasks until the end of the work day.

As COVID has weakened the interest and availability of work crews, the DOC has pivoted to supplying workers through Vermont Correctional Industries for municipal development projects. Previous reporting has uncovered that the Winooski School District used incarcerated labor through their contractor ReArch in a recent school redevelopment project.

Given Vermont communities’ widespread use of work crews, there is an unavoidable financial pressure to make sure people are incarcerated to fill labor needs.

Arizona Department of Corrections Director David Shinn described incentives to imprison people in Arizona, pointing out that the services the DOC provides using incarcerated labor “simply can’t be quantified at a rate that most jurisdictions could ever afford.” He also issued a warning to legislators: “If you were to remove these folks from that equation, things would collapse in many of your counties, for your constituents.” One of the primary purposes of the US carceral system is to fill the demand for involuntary labor rooted in our history of slavery. While COVID-19 slowed the DOC’s work crews, it is clear that many of our local municipalities, nonprofits, and utilities depend on exploiting their fellow Vermonters through low-paid, incarcerated labor. Our communities and economy have been built upon a foundation of exploitation: free labor from captive people.