In the first part of this series, we look at Vermont’s history of exploiting incarcerated people along with recent legislative actions meant to abolish slavery in name only. Read the other parts of this investigative series here.

This November, the Vermont Abolish Slavery and Indentured Servitude Amendment to the Vermont State Constitution will be presented to Vermont voters for approval. The bill intends to update Vermont’s Constitution regarding slavery, clarifying that “slavery and indentured servitude in any form are prohibited.”

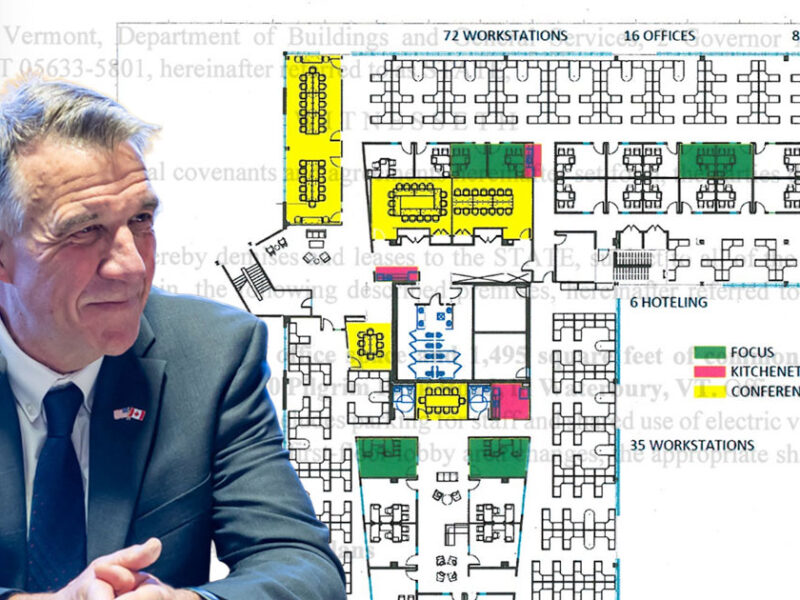

However, this bill does not seem to address the Vermont Department of Correction’s Vermont Offender Work Programs (VOWP), which, while technically voluntary, is considered by many to be modern-day slavery. The program has been used by Vermont state and local governments for decades and championed by politicians from all three political parties. Most recently, The Rake uncovered that a private, for-profit contractor, ReArch, had been using incarcerated labor for Winooski School District’s $60 million school expansion project.

Vermont’s incarcerated workers are all paid far below minimum wage. While their working conditions would be considered illegal if done by private businesses, the State makes an exception for itself. These incarcerated workers are barred from unionizing, their employer is often their landlord, and in some cases, they work like indentured servants in exchange for a shorter sentence, aka “good time.” They are fully at the whim of their employer and jailors, which in this case is the Vermont Department of Corrections.

Across the United States, from Vermont to Arizona and California, advocates are questioning the moral and societal implications of low-paying, coerced prison labor. Recently in California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom helped Senate Democrats reject a bill banning involuntary servitude that would have guaranteed incarcerated workers a minimum of $15 an hour, admitting that if enacted, this would cost the state billions in currently unpaid and underpaid wages.

Around the same time, the Arizona Department of Corrections director admitted that if incarcerated labor were removed from local municipalities, “things would collapse” in many counties.

Vermont’s reliance on using prison labor has many similarities to California, Arizona, and every other state in this country, and this series will look at how Vermont utilizes that labor to its benefit.

The Vermont Department of Corrections’ Incarcerated Labor System

The Vermont Department of Corrections runs seven different prison facilities throughout the state and incarcerates approximately 1,300 people, including several hundred housed at an out-of-state, for-profit prison in Mississippi. These facilities are the Chittenden Correctional Center, Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility, Northeast Regional Correctional Facility (which includes the Caledonia Community Work Camp), Northern State Correctional Facility, Northwest State Correctional Facility, Southeast State Correctional Facility, and Southern State Correctional Facility.

The Vermont prison system has one of the worst racial disparities in the country. A 2021 report from a special state task force found that Black Vermonters are 14 times more likely to be charged with a felony drug crime, and Vermont’s Black population is incarcerated at 10 times the rate of whites. This is in line with what author Michelle Alexander has called the “New Jim Crow,” the national history and trend of disproportionate mass incarceration of Black people. As with the original Jim Crow South, people in prison are afforded few rights or protections, and their safety and health is at the whim of guards and corrections staff.

Vermont’s prisons have been rife with claims of discrimination, harassment, and sexual assault against incarcerated people. A recent investigation by Seven Days showed how abuse and discrimination in Vermont prisons is also rampant for transgender people in prison.

Against this backdrop, once these people are taken away from their families, communities, and place of employment, they have few opportunities to financially support themselves or their families. Moreover, since food and drink from the commissary, some digital media use, and even basic communication with loved ones are not free in prison, most people in prison need to work for income if they can’t rely on an outside source of money to cover their costs.

There are several different ways people in prison can be hired or contracted out by the State to do this, depending on the largesse of DOC staff.

One option is to work in the prison internally, doing many of the tasks that keep facilities running. Another option is to be hired by Vermont Correctional Industries (VCI), which “operates independently, much like a business, out-side of the Department’s General Fund appropriation” and covers all of its costs by selling products to public entities, municipalities, and nonprofits. Finally, if they are deemed particularly low-risk and have extremely good relationships with DOC staff, incarcerated people can get into a work-release program that allows them to work outside the prison, with no supervision, for prevailing wages.

Vermont’s Long History of Coerced State Labor

According to Vermont: A History by Charles T. Morrissey, there is a long history of imprisoned Vermonters being hired out by the State, going back to 1828, when the appointed warden in Windsor paid incarcerated people 25 cents an hour to manufacture a hydraulic pump he had patented. While that was a clear conflict of interest, paid prisoner labor never disappeared from Vermont. Rather, it became highly regulated by state and federal governments.

From the beginning and as early as 1895, one of the biggest fears from private businesses was that the State would compete with them by having access to low-paid workers. This concern has consistently reappeared over the last 130 years.

In Vermont, incarcerated workers’ starting wage has not changed since 1828, but since they are no longer challenging non-incarcerated labor, outside groups have remained silent on the issue. The VCI pay scale has not been updated in over 30 years, since 1988, when the starting wage was 25 cents an hour.

Vermont’s Inmate Work Policy states that work programs can be created and maintained for any of the following reasons: reducing idleness, reducing the cost of incarceration, to give workers basic work experience and training, to make products for the State, to serve as maintenance crews for local municipalities, and to help people in prison secure gainful employment once they are no longer incarcerated.

Vermont law dictates the purpose of these work facilities, which is to enhance the labor pool of private Vermont businesses without directly competing with them and to directly decrease State expenses. Vermont’s goals are to “return value to communities,” “establish good habits of work,” “pursue initiatives with private business to enhance offender employment opportunities,” and “reduce the cost of operations of the Department of Corrections and of other State agencies.” One Arizona editorial board called this type of arrangement “‘modern day slavery.”

In Vermont as well as nationally, wages to people in prison are not guaranteed and can be siphoned for numerous reasons, whether to make payments to victims, to defray the “cost of offender maintenance,” to provide for an incarcerated Vermonter’s dependants, or to cover the cost of “books, instruments, and instruction not supplied by a correctional facility.”

Incarcerated workers are captive, exploited workers. They cannot form a union or organize for stronger employee protections, can be fired at will with no other employment options, and are ineligible to receive unemployment. There is no written process for disciplining workers, and there is no progressive discipline. Their employment is entirely at the discretion of their boss, who can be their prison guard, or in some cases, a fellow incarcerated person who has been made their supervisor. On top of this, any workers hurt on the job cannot sue for damages.

Vermont’s Anti-Slavery Amendment Won’t End Coerced DOC Labor

The Vermont Department of Corrections sees no conflict between the recent bill to abolish slavery from the state constitution and their own labor practices. In contrast, some proponents believe that the bill could open the door to lawsuits regarding prison labor.

Yet even many proponents of the bill, such as former state senator Debbie Ingram, seem unconcerned with exploitative prison labor, admitting that abolishing prison labor is not part of the bill’s goal, but rather that it was about “the moral principle of making a statement that slavery is morally reprehensible.”

According to a recent VTDigger article, Rachel Feldman, DOC spokesperson, reiterated that people who are incarcerated are not being forced to work, but she did not address the numerous coercive circumstances – from lack of activities in prisons to exorbitant fees for communication with loved ones or to buy basic personal necessities – requiring people who are incarcerated to work in order to maintain their health or meet basic needs.

A national report for the ACLU spells out how voluntary work in prisons often amounts to coercion and exploitation that is similar to slavery. It found that more than 76% of incarcerated workers nationally say that “they are required to work or face additional punishments such as solitary confinement, denial of opportunities to reduce their sentence, and loss of family visitation, or the inability to pay for basic life necessities like bath soap.”

It is estimated that in the United States, the most heavily incarcerated country in the world, prisoners produce over 11 billion dollars worth of goods and services. They are paid on average 76 cents an hour.

While this first glance of labor practices for people in prison is troubling in its own right, each subsequent article in this five-part series will look deeper into the multiple ways incarcerated Vermonters are exploited. The second part will investigate how the DOC relies on incarcerated workers to keep prisons open and financially viable. Parts three and four will examine how telecommunication companies and food vendors exploit the few financial resources available to people in prison by expanding monopolies on post-Covid communication and access to food respectively. And lastly, part five will discuss how local municipalities, non-profits, and even for-profit companies benefit from prison labor.